Semantic variation and sociolinguistics

20 Aug 2020Most of my work is somehow about semantic change, be it long-term or over the course of a single interaction. In the past, I’ve characterized semantic change as simply semantic variation over time. A word means one thing at one point in time; it means something else later. That’s change. But, after two years of working on this topic, it’s finally clear to me that that the relationship between that kind of change and variation as sociolinguists talk about it is a little more complicated.

In sociolinguistics, variation isn’t traditionally defined in a way that would include variation in the meaning of a word (be it between speakers or over time). In fact, variationist sociolinguistics doesn’t usually concern itself with semantics at all (which is probably part of the reason I haven’t recognized this discrepancy until now), but even if you extend the notion used in studies of phonological or syntactic variation to semantics, it wouldn’t necessarily include differences in the meaning of a given word.

Making this extension is not easy for reasons I’ll explore below, and it seems that Ruqaiya Hasan is probably among the most notable linguists who have attempted it in a serious way. This post is mainly a summary of the second chapter of her book Semantic Variation: Meaning in Society and in Sociolinguistics, which sets out her vision for including semantics in the kinds of variation sociolinguists look at.

Dr. Hasan retired as emeritus professor from the Macquaire University in Sydney in 1994; she had had a full career by the time this collected works volume was published in 2009. In the first two chapters, which serve as an introduction to the volume, she writes with some degree of frustration at certain inflexibilites and dogmas in mainstream sociolinguistics. You can tell that there are certain things she would have liked to see change over her career and, seeing that they haven’t, these two chapters feel like something of a guide for future travelers.

The first chapter, Wanted: a theory for integrated sociolinguistics, argues broadly for Systematic Functional Linguistics (SFL) as a more appropriate linguistic theory from which to conduct sociolinguistic research. Chapter 2, On Semantic Variation, talks specifically about how SFL makes semantic variation possible as an object of sociolinguistic inquiry.

The problem with semantic variation

It is not always very explicit what sociolinguists mean by variation. Some have insisted that it remain analyzed, used in a pretheoretical way. This usually comes with some version of the advice that sociolinguistic variants are different ways of saying the same thing. Hasan finds this problematic. It raises a lot of immediate questions: What is the thing that is the same? What constitutes different ways of saying? In particular, this intuitive definition leaves unanswered the question of whether semantic variation is even possible.

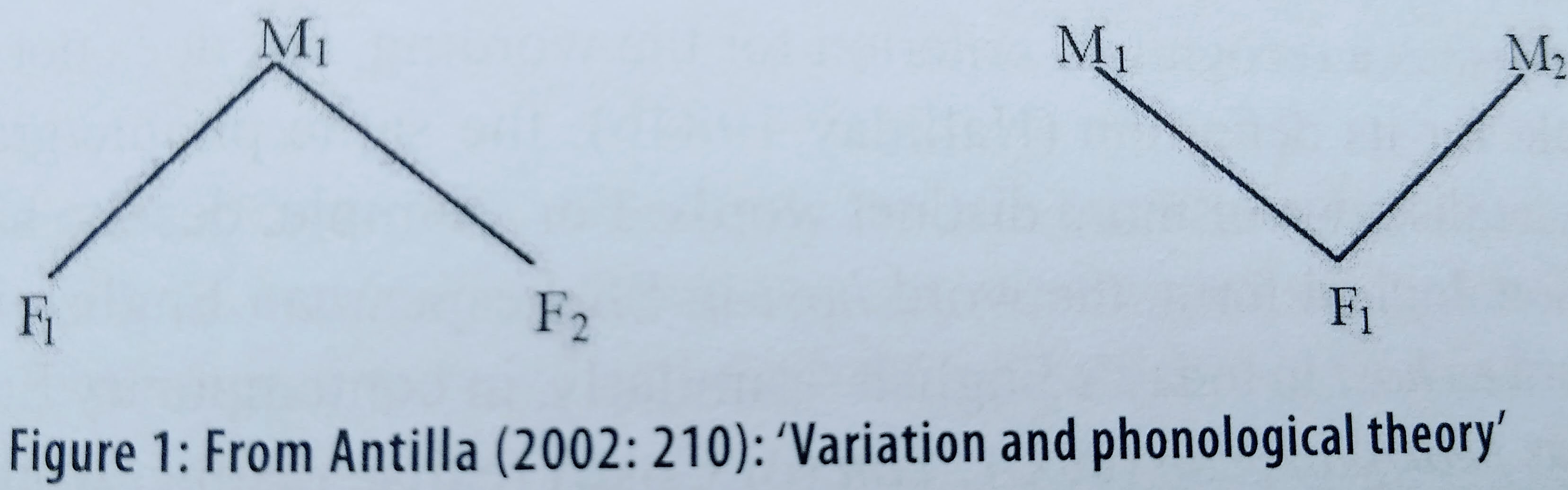

Antilla (2002) makes explicit what seems to be the most common assumed answers to these questions. Variation is a form-meaning relation of the kind found on the left, where two different forms correspond to a single meaning. When a single form corresponds to two different meanings, that’s not variation, it’s ambiguity.

Now, the form/meaning distinction here is not to be interpreted strictly as syntax/semantics, but rather indicating two different levels of linguistic analysis. Hasan talks about this with the SFL concept of realization. For example, a phonological form realizes a phoneme. Two different speech sounds can realize the same word if they are, for example, spoken by New Yorkers of two different social classes.1

Now the problem with semantic variation becomes clear when you consider the classical linguistic hierarchy:

- Phonetics

- Phonology

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Semantics

Since semantics is at the top, it can’t ever play the role of form. There is no X such that two different (semantic) meanings can realize the same X.

Small caveat: this isn’t really quite true. If you consider the function of an utterance, it’s certainly possible to use an utterance with two different semantic meanings that have the same functional goal. Perhaps this is because we left off the top level of linguistic analysis: pragmatics.

- Can you open the window?

- Open the window.

- It’s a bit stuffy in here…

These there sentences are clearly semantically different (at least in classical truth-conditional accounts of meaning). But they might very well have the same pragmatic function (to get someone to open the window).

But the relationship between pragmatics and semantics isn’t as clearly one of realization, as is a speech sound realizing a word or a syntactic construction realizing a semantic unit. This is why Hasan prefers to drop the hierarchy requirement and consider different aspects of meaning.

The SFL solution

In Systemic Functional Linguistics (at any rate in one version of Michael Halliday’s SFL), there are there aspects of the social context of speech:

- field - the social action the speech is being used to achieve

- tenor - the social relation between participants

- mode - the physical and semiotic method of communication

These correspond broadly to three so-called metafunctions of language: ideational, interpersonal, and textual.

The language-level metafunctions are realized by utterance-level linguistic choices which function to achieve goals in the realm of each of the three aspects of social context. Consider these examples from Hasan’s study of semantic variation in child-directed speech:

- Let’s wash your hands before you touch that sandwich.

- You must wash your hands before you touch that sandwich.

- Let’s not play with those marbles when Andrew is crawling about.

In these examples, (1) and (2) have the same ideational function—they seek to get the child to wash their hands. But their interpersonal function is different because they vary in tenor. Likewise, (1) and (3) have the same interpersonal function but differ in ideational function.

Are other solutions possible?

I think Hasan is right that a linguistic theory with the traditional analytic strata is a poor choice for sociolinguistic analysis of semantic variation, especially when coupled with a strictly truth-conditional semantics. But I’m not sure that I’m convinced that SFL is the be-all and end-all solution. And, to be fair, Hasan herself admits that there are probably other solutions.

I am also skeptical of Antilla’s theorizing of the prethoretical different ways of saying the same thing.

If one word, F1 can mean two different things, say M1 and M2 sure, that could be ambiguity (as in the case of “bank” meaning river bank and financial institution).

But it could also be variation. If when I say “awesome” I mean cool, fun, good and my great aunt means inspiring of awe, that seems to me like it should be considered variation. If when I’m at work and I say “transformer” and I mean some kind of neural network thingy and when I’m at home talking to my little nephew I mean a science fiction mecha, that seems like variation, not (or not merely) ambiguity.

To me, and indeed to a lot of sociolinguists,2 variation is intimately wrapped up in semantic change. Not just because, as I naively put it, change is simply variation over time, but because variation is what makes change possible (and perhaps vice versa). And when people talk about semantic change, be it historic change or more short-term semantic accommodation, we are usually talking about a change in the meaning of a word—one form with multiple meanings over time.

That said, I’ve come to believe that the one-word-multiple-meanings paradigm is actually rather limited in its ability to describe the semantic change that’s going on around us. And I’m interested in the kind of variation (and indeed change) that Hasan describes in the child-directed speech work, where some aspect of meaning is constant while some other aspect of meaning varies. I think there is good motivation here for finding ways to model aspects of meaning computationally. I’m not sure how to do that, but maybe we need to think more seriously (as Hasan suggests sociolinguists do) about starting with some less formal (more descriptive) theory of meaning like SFL.

References

- Antilla, A. (2002). Variation and phonological theory. In J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill and N. Schilling-Estes (eds).

- Hasan, R. (2009). Collected works of Ruqaiya Hasan. Vol. 2, Semantic variation: Meaning in society and in sociolinguistics. Equinox.

- Labov, W. (1966). The social stratification of English in New York City. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1985). Linguistic Change, Social Network and Speaker Innovation. Journal of Linguistics, 21(2), 339–384. JSTOR.