08 Aug 2023

It’s been a while since I posted here, but I thought it’s time for a small update.

First, I successfully defended my PhD thesis Semantic change in interaction: Studies on the dynamics of lexical meaning in May.

The thesis is a compilation of 7 papers, which collectively try to answer two questions:

- How does semantic coordination at the level of interaction relate to lexical change on the community level?

- Why does word meaning change across time and context?

Of course these are really broad and I’m not trying to give a full definitive answer in the thesis,

but the kappa (available at the link above)

tries to relate each of the individual papers in the compilation to those big questions.

The kappa also gives background on the theory and methods that are used in the thesis.

I tried to make a serious effort to write it in a way that is interesting to people who

aren’t in my tiny field.

The papers themselves aren’t included in the PDF version of the thesis,

but they are all freely available online and are better read in their original conference paper formatting anyway:

- Chapter 7 – What do you mean by negotiation? Annotating social media discussions about word meaning

- Chapter 8 – Classification Systems: Combining taxonomical and perceptual lexical meaning

- Chapter 9 ~ Coordinating taxonomical and observational meaning: The case of genus-differentia definitions.

- Chapter 10 – Describe me an Aucklet: Generating Grounded Perceptual Category Descriptions.

- Chapter 11 – Personae under uncertainty: The case of topoi.

- Chapter 12 – Conditional Language Models for Community-Level Linguistic Variation.

- Chapter 13 – Semantic shift in social networks

I defended my the thesis on April 20th.

Casey Kennington was the opponent,

and the committee consisted of

Hana Filip,

Jakub Szymanik, and

Dana Dannells.

I couldn’t have asked for a more perfect culmination to the last

several years of research and life, so a big thank you to everyone involved.

Change is Key!

Starting in August of this year I’m working as a researcher

in the Change is Key! project,

lead by Nina Tahmasebi.

Among other things, I’ll be working on datasets and models

for fine-grained semantic change detection.

I’m really excited to work with the many brilliant people in the CiK project.

20 Aug 2020

Can there be a more improper linguistics for doing sociolinguistics than the one which sociolinguists have adopted?

Ruqaiya Hasan, On semantic variation

Most of my work is somehow about semantic change, be it long-term or over the course of a single interaction.

In the past, I’ve characterized semantic change as simply semantic variation over time.

A word means one thing at one point in time; it means something else later. That’s change.

But, after two years of working on this topic, it’s finally clear to me that that the relationship between that kind of change and variation as sociolinguists talk about it is a little more complicated.

In sociolinguistics, variation isn’t traditionally defined in a way that would include variation in the meaning of a word (be it between speakers or over time).

In fact, variationist sociolinguistics doesn’t usually concern itself with semantics at all (which is probably part of the reason I haven’t recognized this discrepancy until now), but even if you extend the notion used in studies of phonological or syntactic variation to semantics, it wouldn’t necessarily include differences in the meaning of a given word.

Making this extension is not easy for reasons I’ll explore below, and it seems that Ruqaiya Hasan is probably among the most notable linguists who have attempted it in a serious way.

This post is mainly a summary of the second chapter of her book Semantic Variation: Meaning in Society and in Sociolinguistics, which sets out her vision for including semantics in the kinds of variation sociolinguists look at.

Dr. Hasan retired as emeritus professor from the Macquaire University in Sydney in 1994; she had had a full career by the time this collected works volume was published in 2009.

In the first two chapters, which serve as an introduction to the volume, she writes with some degree of frustration at certain inflexibilites and dogmas in mainstream sociolinguistics. You can tell that there are certain things she would have liked to see change over her career and, seeing that they haven’t, these two chapters feel like something of a guide for future travelers.

The first chapter, Wanted: a theory for integrated sociolinguistics, argues broadly for Systematic Functional Linguistics (SFL) as a more appropriate linguistic theory from which to conduct sociolinguistic research. Chapter 2, On Semantic Variation, talks specifically about how SFL makes semantic variation possible as an object of sociolinguistic inquiry.

The problem with semantic variation

It is not always very explicit what sociolinguists mean by variation. Some have insisted that it remain analyzed, used in a pretheoretical way. This usually comes with some version of the advice that sociolinguistic variants are different ways of saying the same thing.

Hasan finds this problematic. It raises a lot of immediate questions: What is the thing that is the same? What constitutes different ways of saying?

In particular, this intuitive definition leaves unanswered the question of whether semantic variation is even possible.

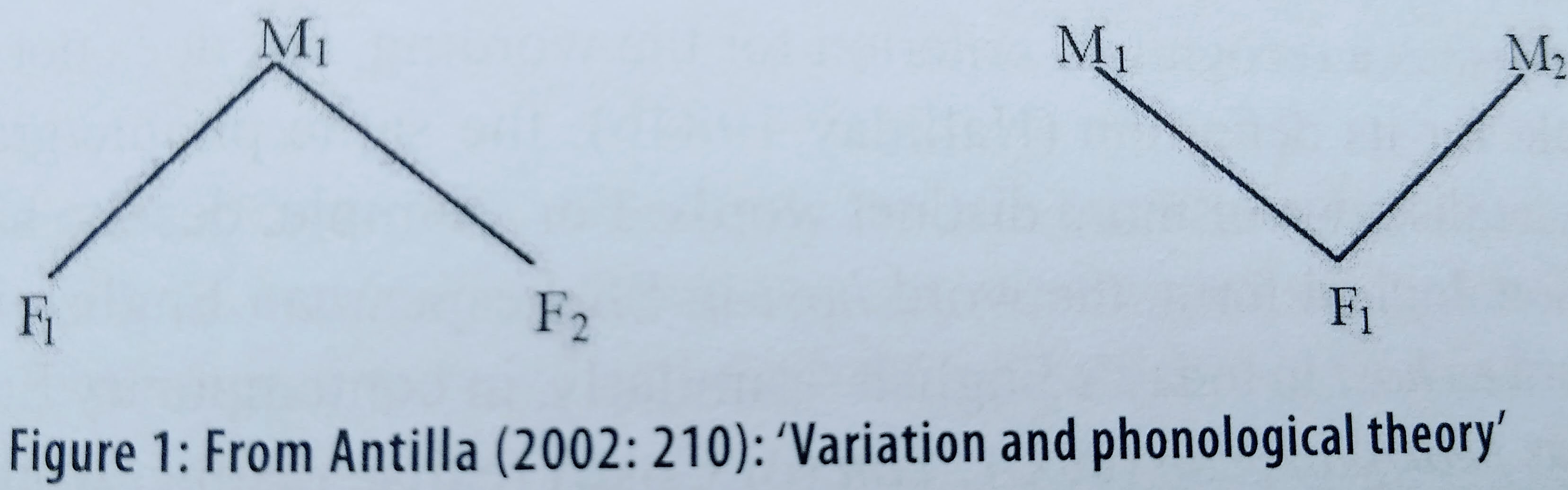

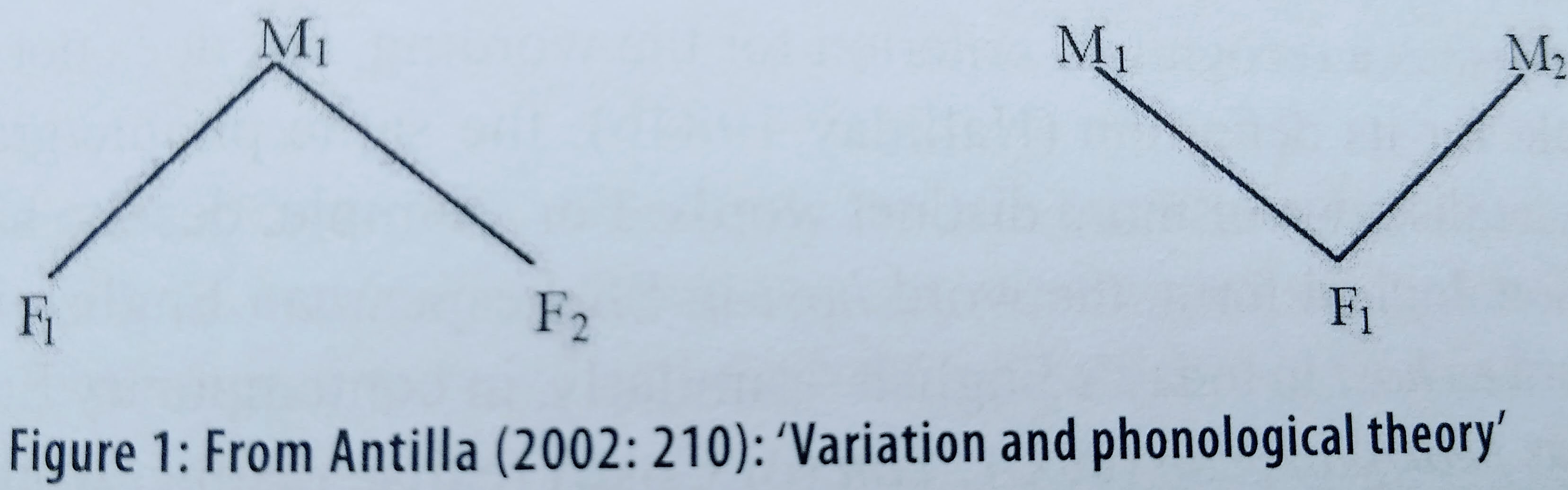

Antilla (2002) makes explicit what seems to be the most common assumed answers to these questions. Variation is a form-meaning relation of the kind found on the left, where two different forms correspond to a single meaning. When a single form corresponds to two different meanings, that’s not variation, it’s ambiguity.

Now, the form/meaning distinction here is not to be interpreted strictly as syntax/semantics, but rather indicating two different levels of linguistic analysis.

Hasan talks about this with the SFL concept of realization. For example, a phonological form realizes a phoneme. Two different speech sounds can realize the same word if they are, for example, spoken by New Yorkers of two different social classes.

Now the problem with semantic variation becomes clear when you consider the classical linguistic hierarchy:

- Phonetics

- Phonology

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Semantics

Since semantics is at the top, it can’t ever play the role of form. There is no X such that two different (semantic) meanings can realize the same X.

Small caveat: this isn’t really quite true. If you consider the function of an utterance, it’s certainly possible to use an utterance with two different semantic meanings that have the same functional goal. Perhaps this is because we left off the top level of linguistic analysis: pragmatics.

- Can you open the window?

- Open the window.

- It’s a bit stuffy in here…

These there sentences are clearly semantically different (at least in classical truth-conditional accounts of meaning). But they might very well have the same pragmatic function (to get someone to open the window).

But the relationship between pragmatics and semantics isn’t as clearly one of realization, as is a speech sound realizing a word or a syntactic construction realizing a semantic unit.

This is why Hasan prefers to drop the hierarchy requirement and consider different aspects of meaning.

The SFL solution

In Systemic Functional Linguistics (at any rate in one version of Michael Halliday’s SFL), there are there aspects of the social context of speech:

- field - the social action the speech is being used to achieve

- tenor - the social relation between participants

- mode - the physical and semiotic method of communication

These correspond broadly to three so-called metafunctions of language: ideational, interpersonal, and textual.

The language-level metafunctions are realized by utterance-level linguistic choices which function to achieve goals in the realm of each of the three aspects of social context. Consider these examples from Hasan’s study of semantic variation in child-directed speech:

- Let’s wash your hands before you touch that sandwich.

- You must wash your hands before you touch that sandwich.

- Let’s not play with those marbles when Andrew is crawling about.

In these examples, (1) and (2) have the same ideational function—they seek to get the child to wash their hands. But their interpersonal function is different because they vary in tenor. Likewise, (1) and (3) have the same interpersonal function but differ in ideational function.

Are other solutions possible?

I think Hasan is right that a linguistic theory with the traditional analytic strata is a poor choice for sociolinguistic analysis of semantic variation, especially when coupled with a strictly truth-conditional semantics.

But I’m not sure that I’m convinced that SFL is the be-all and end-all solution. And, to be fair, Hasan herself admits that there are probably other solutions.

I am also skeptical of Antilla’s theorizing of the prethoretical different ways of saying the same thing.

If one word, F1 can mean two different things, say M1 and M2 sure, that could be ambiguity (as in the case of “bank” meaning river bank and financial institution).

But it could also be variation. If when I say “awesome” I mean cool, fun, good and my great aunt means inspiring of awe, that seems to me like it should be considered variation. If when I’m at work and I say “transformer” and I mean some kind of neural network thingy and when I’m at home talking to my little nephew I mean a science fiction mecha, that seems like variation, not (or not merely) ambiguity.

To me, and indeed to a lot of sociolinguists, variation is intimately wrapped up in semantic change. Not just because, as I naively put it, change is simply variation over time, but because variation is what makes change possible (and perhaps vice versa).

And when people talk about semantic change, be it historic change or more short-term semantic accommodation, we are usually talking about a change in the meaning of a word—one form with multiple meanings over time.

That said, I’ve come to believe that the one-word-multiple-meanings paradigm is actually rather limited in its ability to describe the semantic change that’s going on around us.

And I’m interested in the kind of variation (and indeed change) that Hasan describes in the child-directed speech work, where some aspect of meaning is constant while some other aspect of meaning varies.

I think there is good motivation here for finding ways to model aspects of meaning computationally.

I’m not sure how to do that, but maybe we need to think more seriously (as Hasan suggests sociolinguists do) about starting with some less formal (more descriptive) theory of meaning like SFL.

References

- Antilla, A. (2002). Variation and phonological theory. In J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill and N. Schilling-Estes (eds).

- Hasan, R. (2009). Collected works of Ruqaiya Hasan. Vol. 2, Semantic variation: Meaning in society and in sociolinguistics. Equinox.

- Labov, W. (1966). The social stratification of English in New York City. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1985). Linguistic Change, Social Network and Speaker Innovation. Journal of Linguistics, 21(2), 339–384. JSTOR.

28 Sep 2018

people say words //

words mean things //

sometimes the same word means different things //

why's that?

This is the first blog post I’m making as an official PhD student!

I’m still figuring things out,

but so far I know my topic has something to do with semantic change—how

word meanings shift over time.

Semantic change is part of a broader category of phenomena I’ll call semantic variation.

When the same word means two different things,

that’s an example of semantic variation.

Naturally, change is just variation over time.

When you think about the same word meaning two different things,

polysemy (or homonymy) is probably the first thing that comes to mind.

Originally I included polysemy in this list,

but I actually think it’s different from

the kind of thing I’m talking about in an important way.

Polysemy is when the same word can be used to mean two different things.

Take the word bank, which has several possible meanings.

If I say to you “let’s have lunch down by the bank”,

I could be referring to a riverbank,

or I could be talking about a bank-bank—somewhere you keep money.

But I’m interested in variation in the semantics of a word as a whole.

The distinction I’m making here is related to Herman Paul’s

occasional meaning vs. usual meaning,

or perhaps more closely related to the more recent notion of

situated meaning vs. meaning potential.

Polysemy represents variation in situated meaning,

whereas I’m talking about differences in meaning potential.

But I’m not too familiar with these concepts yet…

blog post for another day, perhaps.

Anyway, here’s my list of (the?) four kinds of semantic variation:

- Diversity – differences between speech communities

- Style – differences between individuals

- Change – changes in speech communities

- Adaptation – changes made during a dialogue

One - Semantic Diversity

Here’s where I say something about common ground,

an idea developed by the psycholinguist Herbert H. Clark

and others in the ’90s.

Common ground is a body of knowledge shared among some group of people.

It’s related to the concept of

common knowledge,

where everyone knows a thing,

and also everyone knows that everyone knows it,

and everyone knows that everyone knows it

(and so on).

Common ground needs to be based on something—there

needs to be a reason for everyone to believe we’re all on the same page.

For example,

if you and I were to watch a tennis match together,

certain facts,

such as who won the match,

are grounded (i.e. part of the common ground) between us.

The event of watching the match serves as a basis

for this common ground.

This is what Clark calls a perceptual basis.

There’s another kind of basis called a communal basis,

which grounds knowledge between individuals

based on their belonging to the same community.

For example,

a nurse may assume that a doctor knows difference

between a humerus and a femur

based on their joint membership

in a community of medical professionals.

Communal bases are what we rely on

to ground linguistic knowledge,

such as (surprise!) the meaning of words.

In this framework,

languages, dialects,

the jargon shared by communities of practice,

the unique set of inside jokes shared with your immediate family

or a close circle of friends—all

these things are the same kind of thing

as far as common ground is concerned.

So, communities come first

(conceptually, at least)

and languages are just the linguistic common ground

of the speech community.

And each of these communities

(sometimes nested, sometimes overlapping)

may have different or similar understandings

(or no understanding at all)

of the meaning of any given word.

Two - Semantic Style

Usually when people talk about linguistic style

it has to do with word choice,

or how an individual tends to construct sentences syntactically—the

sorts of things that contribute to tone and register.

But I think there’s good reason to believe

that style is also involved in the meaning of words.

Here’s an example from Barbara Johnstone’s The Linguistic Individual:

I once stayed with my sister during a week when, just having moved to

a new town, she made a number of phone calls inquiring about goods

and services. During one of these conversations, I heard her begin a

response with “Aaahh,” a drawn-out /a/ made lower and further back in

her mouth than the /a/ she used in words such as father or hot and

uttered at a low and very slowly falling pitch. I at once thought of our

father, who makes exactly the same noise in the same conversational

slot in phone conversations of the same sort. Aaahh is a small but

unmistakable feature of his individual way of sounding. It means “I think

I understand what you’ve said, and, if I’ve understood you correctly,

I’m disappointed. Aaahh is the beginning of a rejoinder to a statement

like “We do carry folding directors’ chairs , and they’re $175 each” or

“We’ll be able to collect your bulky trash in two weeks or so.”

Now, Johnstone understood her sister’s Aahhh immediately

because she belongs to a speech community where

its meaning is common ground (i.e., her immediate family),

but how did the person on the other end of the phone understand it?

A naive view of common ground

might lead you to think it wouldn’t be understood at all.

Not so.

For one thing, Johnstone describes how Aaahh always comes

with a translation when her father uses it—a

“synchronic repetition, in a more conventional form”.

So, while there may be no common ground about

Aaahh itself,

listeners understand what he means by it

because there is common ground around

the meaning of other expressions that accompany it.

There’s an interesting question here about whether semantic style

is truly variation in meaning potential,

or if it takes advantage of meaning potential

to produce a different situated meaning.

My feeling is that stylistic variation

can have its source in meaning potential,

but something to think about more later…

Three - (Historic) semantic change

New words are coined, and the meaning of existing words change over time,

even within the same speech community.

There’s a lot to say about how and why this happens—we

know, for example,

that various social and communicative pressures

contribute to the evolution of word meaning,

and that there are certain patterns of semantic shift

that words tend to follow.

In a previous post

I described some recent work that measures how words changing over time.

I’m particularly interested

in how other kinds of semantic variation

influence historic change.

For example,

it’s common far a new interpretation of a word

to start in a smaller speech community

and gain more widespread usage over time.

Likewise, facets of an individual’s linguistic style

may be picked up by others

(like how Johnstone’s sister uses her dad’s Aaahh)

and in that way contribute to historic change

within a community.

Common ground can be useful

for thinking about historic semantic change, too.

What it means for historic semantic change to have taken place

(in a given community)

is that the new meaning is available to speakers

without having to use the dialogue itself

to create it.

This brings us to the final kind of semantic variation.

Four - Semantic adaptation

Semantic adaptation is change that occurs over the course of a dialogue.

Every dialogue starts off with some shared semantic understanding—both

people speak the same language, say.

But the meanings available in their communal common ground

may be rather imprecise.

Or it perhaps there’s no built-in way of

referring to some concept that’s important

in the current discussion.

As they converse,

participants collaborate to refine what words mean

in service of the present dialogue.

Here’s an example from a psychology-style experiment

where participants were asked

to participate in a collaborative challenge

where they had to refer to some pictures of objects.

A: A docksider. B: A what?

A: Um.

B: Is that a kind of dog?

A: No, it’s a kind of um leather shoe, kinda preppy pennyloafer. B: Okay okay got it

In the remainder of the experiment,

both A and B referred this card as the pennyloafer.

A pennyloafer is (I think) a different shoe from a docksider.

Perhaps A even knows this,

but because of the collaborative nature of communication,

the two agree on a new semantics for pennyloafer which,

for the purposes of this dialogue,

refers to the photo in question.

These kind of agreements—explicit and implicit—let

us adjust the meaning of words

in big ways and small.

Sometimes those adjustments persist

after the current dialogue.

And they may be again introduced

in future discussions

with some of the same people,

and perhaps some different people,

and in this way semantic adaptation,

over time,

can become historic change.

08 Aug 2018

Hej Sverige!

I’m moving to Gothenburg, Sweden at the end of the month to take a PhD position at the University of Gotherburg’s Centre for Linguistic Theory and Studies in Probability (CLASP).

It’s a big move, so I thought I’d take some time to write about what I’ll be doing there before I leave.

Basically, I’ll be taking classes, doing research, and probably teaching (or TAing) some, too.

By the end, I’ll have written a dissertation based on my research and (if all goes well) I’ll get a degree.

All this will take four or five years.

What am I researching?

My research will focus on semantic change.

Semantics is the part of linguistics concerned with meaning.

This includes lexical semantics (what do words mean?) and compositional semantics (how do words combine to make meaningful sentences?).

I think my work will mostly focus on lexical semantics.

I’m particularly interested in looking at the social context of language change.

Sociolinguists have this concept of a speech community – a group of people who share a set of linguistic conventions, such as the meaning of certain words.

Speech communities come in all sizes, from as large as speakers of English to as small as a pair of close friends.

Speech communities can overlap or even “eavesdrop” on each other, resulting in the spread of novel linguistic conventions.

Change in a larger community affect the language spoken in sub-communities.

Conversely, changes made to the language in a sub-community are sometimes adopted by the larger community.

Linguistic variation (differences between communities) and linguistic change (differences within a community over time) are two sides of the same coin.

Both are necessary for understanding questions like where does semantic change come from? and why are some changes adopted more broadly, while others aren’t?

Why does it matter?

So, I obviously think this is all really interesting. I also think it’s really important.

At the risk of going all now more than ever on you, I think it’s clear to anyone who’s visited The Internet in the last 5 or 10 years that we’re far from consistent when it comes to maintaining a productive discourse.

And while I wouldn’t try to deny that there are significant—at times insurmountable—differences of opinion and values out there, I think it’s often the case that we can’t even get at those differences because we’re totally talking past each other.

Vox’s Ezra Klein had a nice example of the kind of thing I’m talking about in his piece about the recent Twitter controversy surrounding some old tweets by journalist Sarah Jeong.

A few years ago, it became popular on feminist Twitter to tweet about the awful effects of patriarchal culture and attach the line #KillAllMen. This became popular enough that a bunch of people I know and hang out with and even love began using it in casual conversation.

And you know what? I didn’t like it. It made me feel defensive. It still makes me feel defensive. I’m a man, and I recoil hearing people I care about say all men should be killed.

But I also knew that wasn’t what they were saying. They didn’t want me put to death. They didn’t want any men put to death. They didn’t hate me, and they didn’t hate men. “#KillAllMen” was another way of saying “it would be nice if the world sucked less for women.” It was an expression of frustration with pervasive sexism. I didn’t enjoy the way they said it, but that didn’t mean I had to pretend I couldn’t figure out what they meant. And if I had any questions, I could, you know, ask, and actually listen to the answer.

Here’s the other thing, though: all that was happening inside my community, which both inclined me towards generosity, and gave me more context for what was going on. If I had been on the outside of it, perhaps my ultimate reaction would’ve been different, perhaps I would’ve let my initial offense drive my interpretation.

The internet lets people from across the world connect, find shared experiences, and build communities.

It also enables interaction between people who have very little in common and may sometimes feel at opposition with each other.

I think that access can be a great force for good—and is something worth preserving—but it can also conttribute to discord with serious real-world implications.

When we’re interpreting language, context is key.

Social context is especially key.

We often don’t get that social context on the internet.

It’s foreign, or faded from memory, or (willfully or otherwise) stripped away.

When a new lexical item like #KillAllMen pops up, it’s in response to communicative need—in this case, the need for a tong-in-cheek way to point out problems caused by the patriarchy.

People who don’t possess that need (e.g. men with no interest in pointing out the patriarchy) may not intuitively interpret it that way.

With a better understanding of how semantic change spreads (particularly on the internet), I think we can make better informed choices about how to organize discussion and build communities in a way that makes diverse voices accessible to everyone.

For example, we can find ways to make the social context necessary for generous interpretation available, while exposing bad-faith provocateurs who feign outrage (i.e. trolls) for what they are.

I don’t want to make it sound like “oh if only we understood each other all our problems would go away”.

There is clearly no shortage of non-linguistic social division in the world today.

But if we can better understand where semantic change comes from, and what accounts for the differences between communities, I think we can give people better tools for contextualizing each other’s speech and at least start discussing those divisions across linguistic communities.

So what does this “research” actually consist of?

I’m planning to take an interdisciplinary approach, grounding my research in cognitive and sociolinguistics theory, and applying tools from computational linguistics and social network analysis.

A lot of my research will using computer models to find and probe phenomena such as semantic change in large-scale corpuses of social media and other internet discourse.

I think it will be a good practice to update this blog regularly as my studies and research progress, so if you’re interested, stay tuned here or follow me on Twitter.

10 May 2018

Google is choosing when how we talk about AI ethics.

On Tuesday, Google demoed an update to its virtual assistant

that calls up businesses on your behalf to book appointments and make reservations.

In the demo, Duplex makes two calls, one to make a hair appointment, and another to reserve a table at a restaurant.

The reservation call is especially impressive because when it turns out the restaurant

will only take reservations for five or more people, Duplex politely takes no as an answer and knows to ask

if there’s likely to be a wait.

It neither conversation did Duplex identify itself as non-human. It even goes so far as to introduce speech disfluencies (ummms and aahs and at least one sassy mmm-hmmmmm)

which Google acknowledges are mostly about sounding more human.

I wouldn’t mind that kind of thing if I know I’m talking to a computer, but it feels like an especially harsh betrayal

to be manipulated into believing an AI is human in that way.

Why did Google, with their armies of PR people, think it was ok to demo a product that misrepresents itself as human

to unwitting service workers?

They knew that this demo would cause a backlash, they just didn’t know how big.

And now they’re getting to find out. So far we have:

- Tech Crunch - Duplex shows Google failing ethical and creative AI design

- PC Mag - Google Duplex is classist: Here’s how to fix it

- The Verge - The selfishness of Google Duplex

- Slate - Am I speaking to a human?

As of a few hours ago CNET is reporting that Google has already started “clarifying”:

We are designing this feature with disclosure built-in, and we’ll make sure the system is appropriately identified. What we showed at I/O was an early technology demo, and we look forward to incorporating feedback as we develop this into a product.

But that doesn’t really answer any of the specific questions I want to have answered:

- does the assistant identify itself as non-human up front, or only when asked?

- can businesses opt out of receiving calls from Duplex?

- what action does Duplex take when the conversation fails?

Instead, it looks like Google is stalling for time. They’re “incorporating feedback”.

In other words, they’re waiting to see what we decide is okay and then they’ll see what they can get away with.

This kind of tactic can be used to shift the overton window on what behaviors we’re ok with from our technology.

Maybe that’s already what’s happening here, even.

One thing is for sure, there are plenty of other questions like “Can computers misrepresent themselves as human? that AI companies want answered.

By presenting their answer at a product demo, they get to set the terms of the discussion.

The tone of that demo (here it is by the way) was clearly projecting this is fine.

If that’s where the conversation starts, maybe we end up closer to that position that we would have otherwise.

That’s clearly what Google’s hoping, anyway.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

In ethics classes, in technology journalism, in science fiction, in conversations with friends, on social media!

We can be talking about these questions. We can decide what we’re ok with and what we’re not.

And we don’t have to accept that just because it seems like some thing already is some way that it always has to be that way.