Measuring semantic shift with word embeddings

18 Mar 2018I just read two interesting papers by William L. Hamilton, Jure Loskovec, and Dan Jurafsky about uisg “diachronic word embeddings” to measure semantic shift.

A word embedding (at least the kind they’re talking about here) is a way of associating words with a vector (a list of numbers) that captures something about the word’s meaning in relation to other words. Here, “diachrotic” means they’re calculating the vector representation with respect to at least two different time periods.

First paper

Diachronic word embeddings reveal statistical laws of semantic change arXiv

In this paper the authors are trying to find a way to capare embeddings across time. The dias is to use a word’s vector representation to see how (or at least how much) it’s changed.

The tricky part is you can’t come right out and compare vectors from separate word embeddings since the vector spaces might be totally misaligned. So they have two ideas for how to get around this.

- Meausre change in similarity between pairs of words. E.g., for two different time periods you measure the semantic similarity between ‘cat’ and ‘dog’. Then you can see if that relationship has changed or stayed the same without having to directoly compare across time periods.

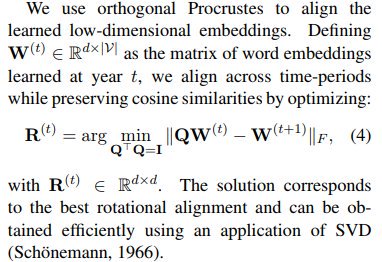

- Align the vector spaces and compare the word’s two vector representations directly. This is the more intuitive solution but requires some tricky math.

I’ll just trust this works… 🙄

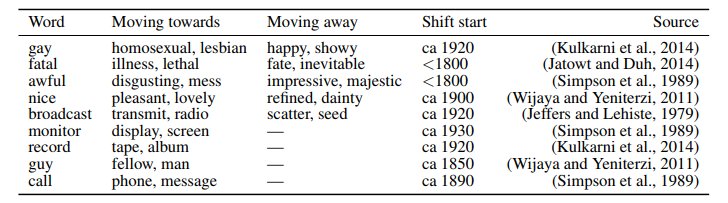

Actually the authors were good enough to test their method out emprically on some well-documented semantic shifts so we can see roughly that it works without decrypting the math 😬

They use these methods to make two observations about semantic change.

- Words that are more polysemous (have multiple meanings) tend to change more and adopt more new meanings over time, and

- words that are used more frequently tend to change less over time.

I think these conclusions make intuitive sense and they’re pretty well aligned with oldschool linguistic theories of semantic shift, so that’s cool.

Next paper!

Cultural shift or linguistic drift? Comparing two measures of semantic change arXiv

Here they define two measures of semantic change that roughly correspond to the two ideas of how to compare vectors across time from the previous paper.

- The “local measure”: Measure the distance between the word and a smallish set of closely related words and see how much those relatioships have changed

- The “global measure”: Measure the distance between the word and its past self directly.

Just like before the first measure is agnostic to the incidentals of the two vector spaces (since you only need to directly compare word vectors from the same time period). The second measure requires vector space alignment between the time periods.

This time though they’re after something a little more subtle… It turns out the global measure is more sensitive to changes in verbs, whereas the local measure reacts more to changes in noun semantics. Why could that be…?

Well, combine this with an established dactrine that says nouns tend to change more for real-world cultural reasons and verbs tend to change more by predictable linguistic processes and you get… possibly a way of detecting the difference between these two kinds of change!

One thing I’m a little skeptical about is that there is a clear-cut distinction between these two kinds of semantic change. To me, cultural shift seems more like a “reason” for semantic change while the “regular processes” seem more like, well, processes. I wonder if verb semantics might change more predictably, but still in reaction to cultural shift, for example.

Anyway, this was some really interesting work! And the authors have been kind enough to make their code and pre-trained vectors available on the project website. I haven’t played with it much yet, but it looks pretty coherent, which is nice.